Share this post

related content

This briefing provides updates to key data from Harm Reduction International's flagship report, The Global State of Harm Reduction. The full report is published every two years, with updates to key data released in between editions of the report. This update also summarises key developments in harm reduction services, funding and drug policy since the launch of the ninth edition of the report in November 2024.

crisis and resilience

This 2025 update presents a stark paradox: while more countries than ever recognise harm reduction in national policy, the sudden withdrawal of US funding in January 2025 has created the most severe threat to global harm reduction services in decades. Services are closing, staff are being lost, and decades of public health progress are at risk.

Yet amid this crisis, extraordinary stories of community resilience have emerged.

Countries with domestic funding have shown the greatest protection. Peer networks have stepped in where formal systems have faltered. Programmes have consolidated resources to maintain life-saving services. This update documents both the devastation and the determination of communities fighting to protect health and human rights for people who use drugs.

Highlights

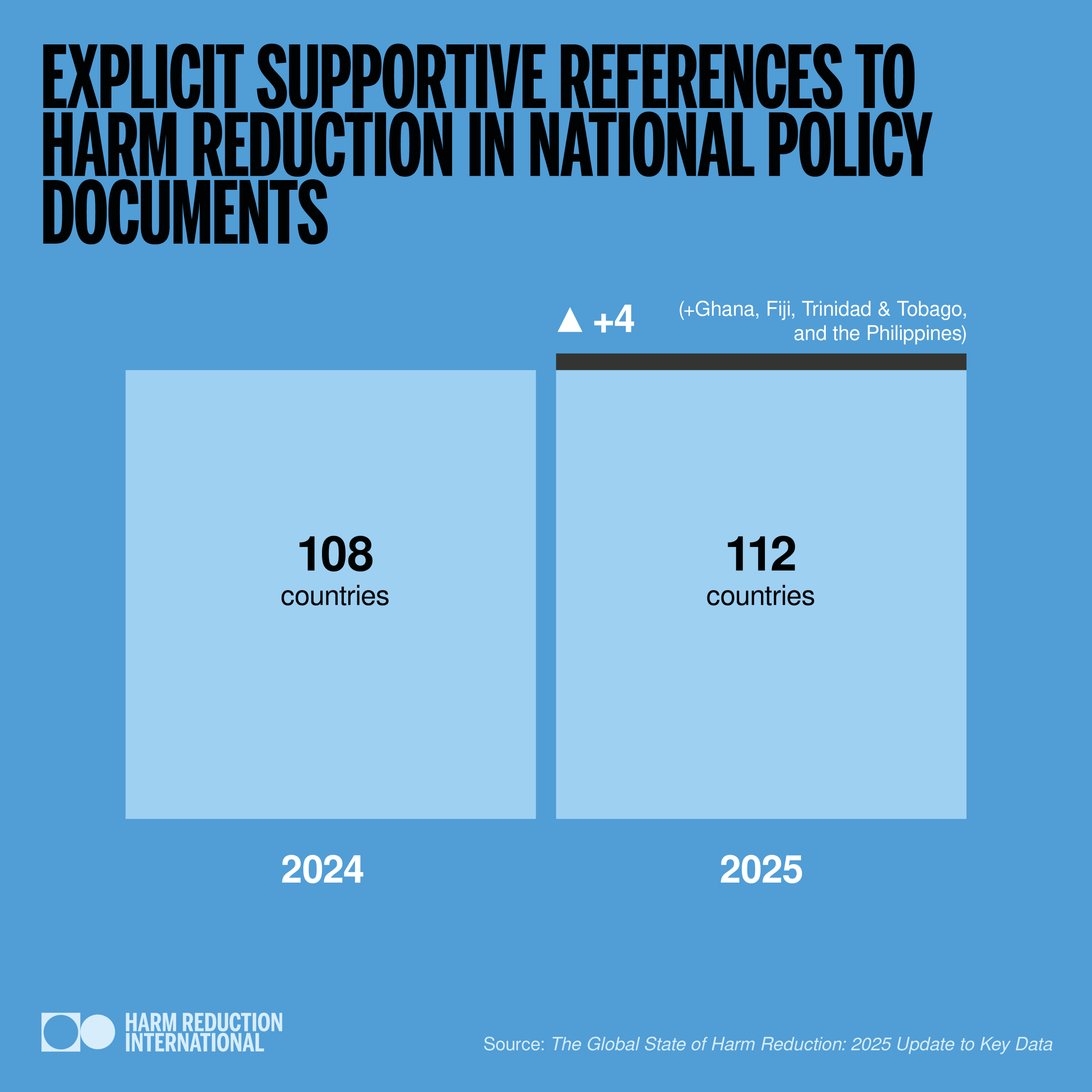

Number of countries with explicit supportive references to harm reduction in national policy documents has increased from 108 to 112. Newly reported countries include Ghana, Fiji, Trinidad & Tobago, and the Philippines.

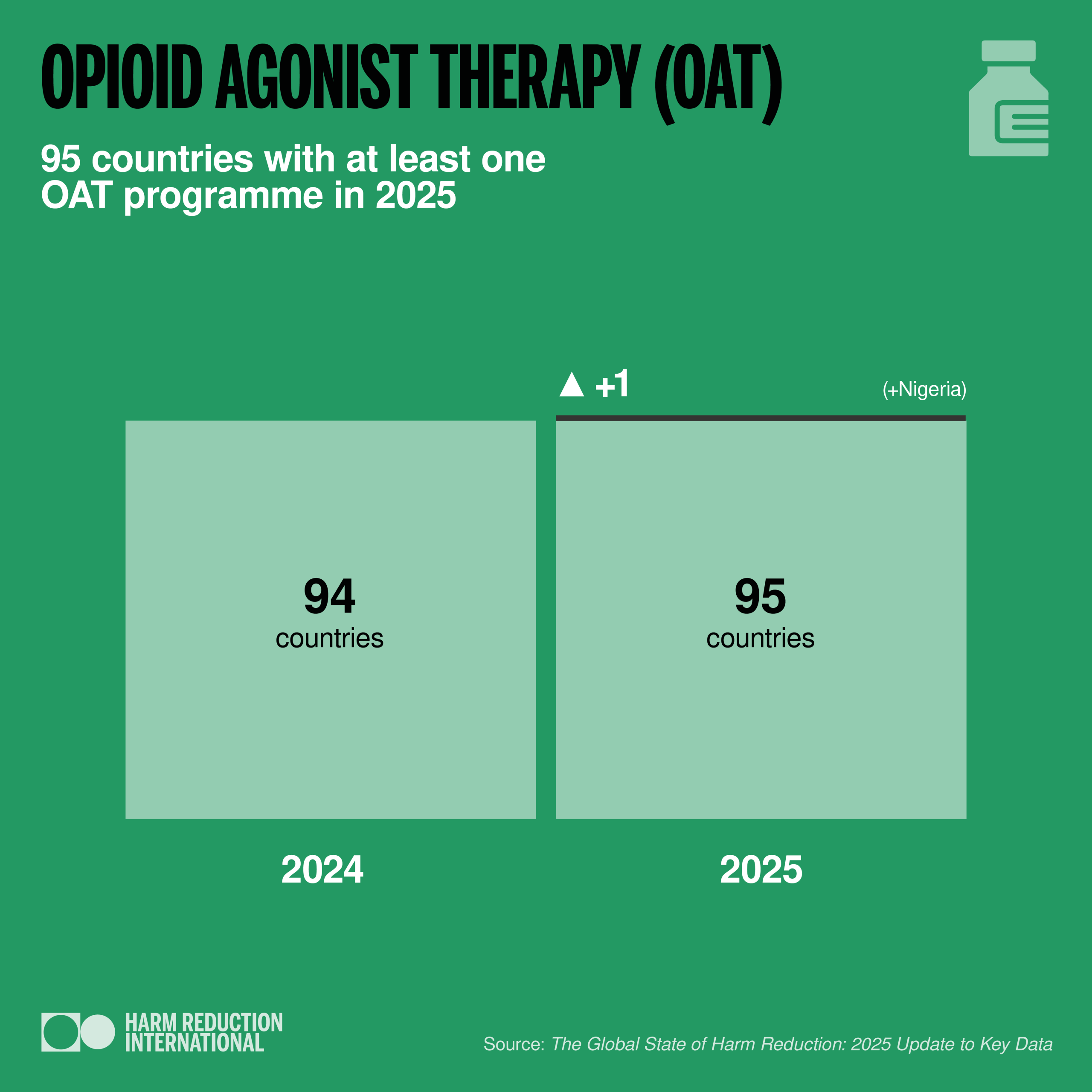

Number of countries with at least one opioid agonist therapy (OAT) programme: 95. Nigeria is the latest country to join this list.

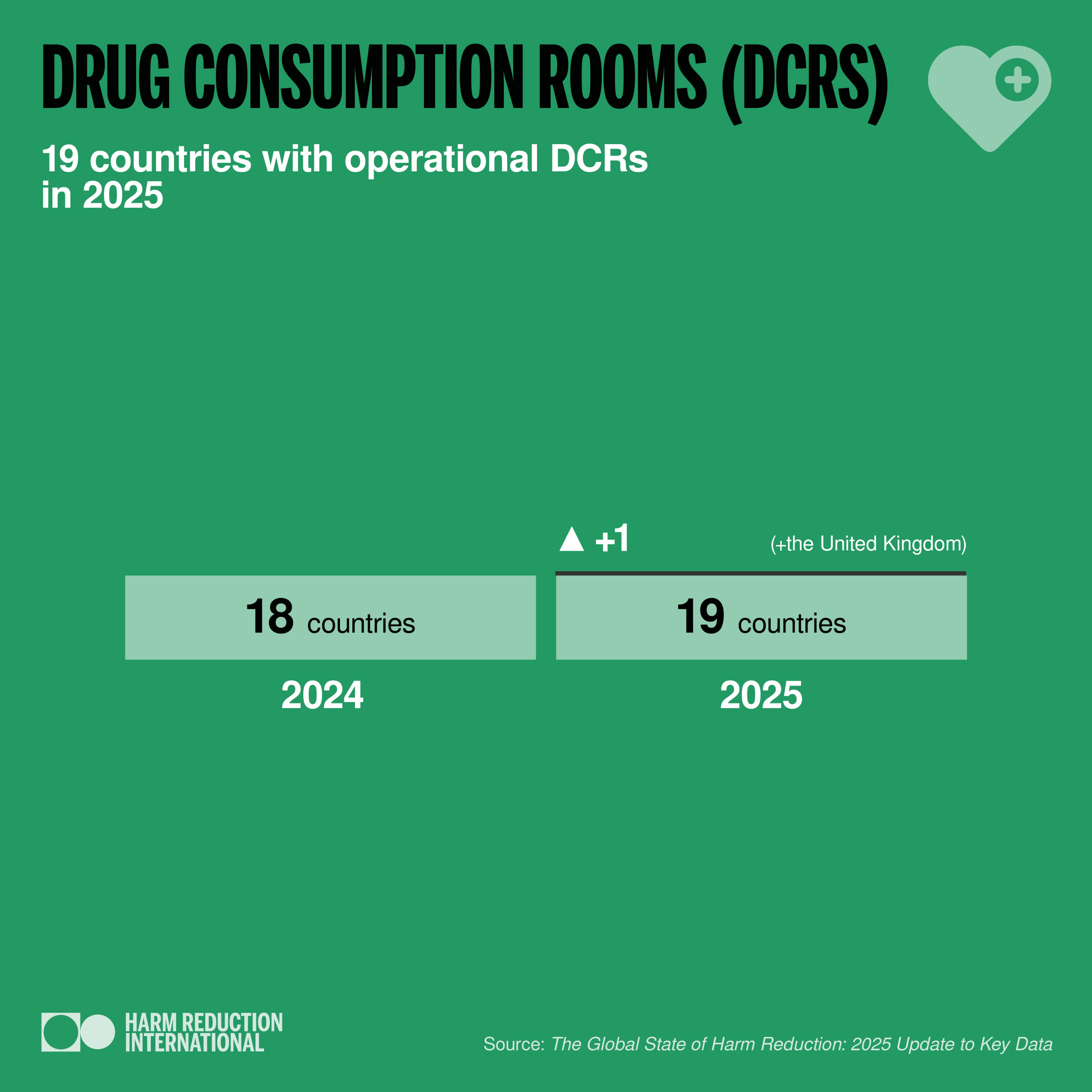

Number of countries with drug consumption rooms (DCRs): 19. The United Kingdom’s first DCR opened in Glasgow, Scotland, named “The Thistle” in 2025.

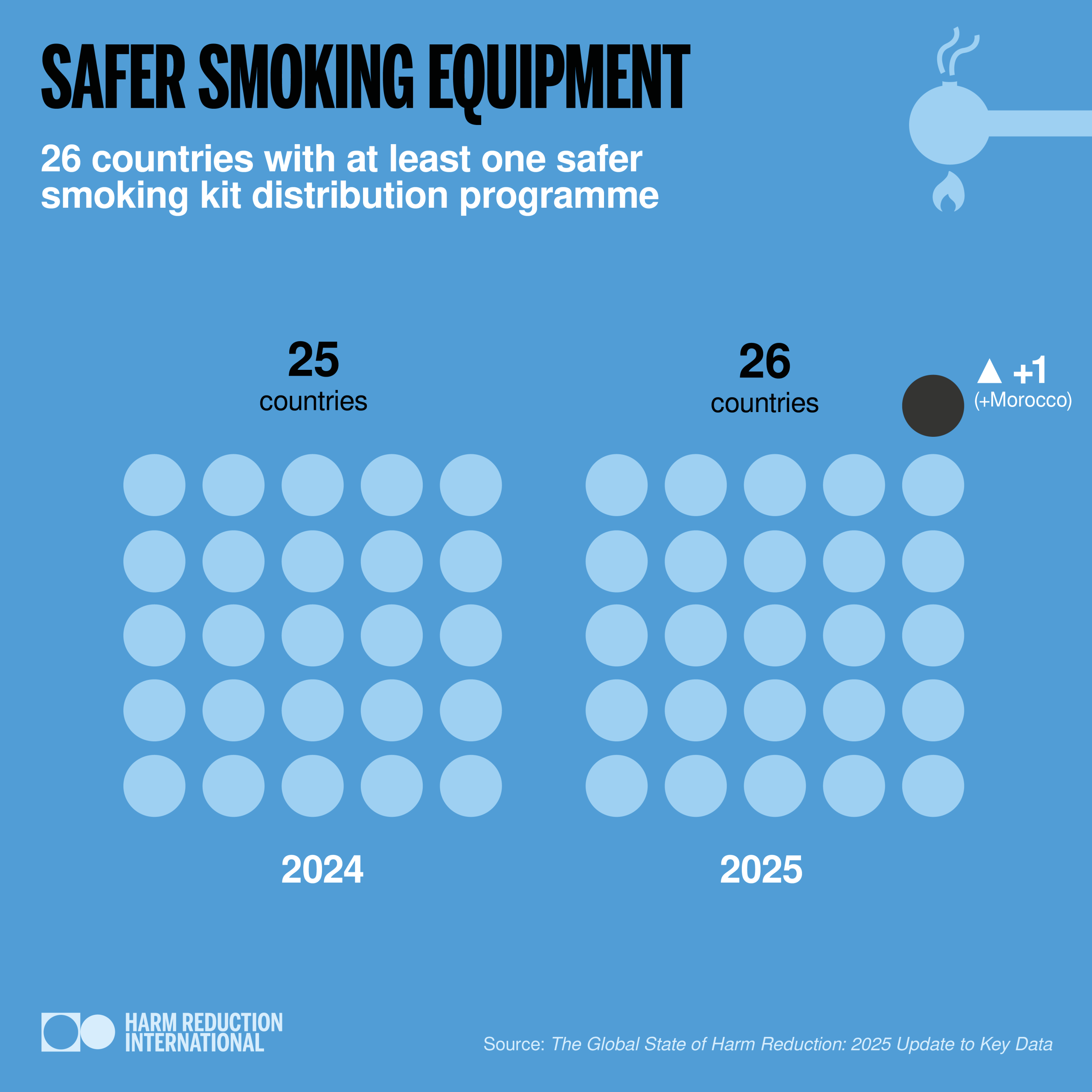

Number of countries that provide safe smoking kits: 26. There is now at least one active programme in Morocco that distributes safer smoking kits.

Harm Reduction Funding

The global health funding landscape has undergone profound upheaval in 2025, with grave consequences for harm reduction. The sustainability of harm reduction programming in many countries is now under serious threat.

Harm Reduction International’s research conducted in September 2025 found that almost 92% of respondents deemed harm reduction to be under threat in their country, with 62% describing the threat as high or critical. Many governments continue to prioritise spending vast amounts on punitive drug policies over investing in policies rooted in health.

Abrupt halt of US Government aid

In January 2025, the United States Government abruptly halted its bilateral and multilateral aid. While some funding was later restored after initial stop-work orders, a large majority of funding was stopped indefinitely.

The United States had been the second-largest harm reduction donor (after the Global Fund) and the largest contributor overall to the Global Fund portfolio. The sudden funding cuts sent shockwaves through low- and middle-income countries reliant on this support, especially those without domestic harm reduction budgets.

As the United States was also the largest contributor to the Global Fund, this triggered a reprioritisation process that reduced country allocations and halted scale-up plans for Grant Cycle 7.

Country-level consequences

The impact has been immediate and far-reaching. In countries receiving direct funding from PEPFAR or other United States agencies, many harm reduction services closed overnight, or were forced to operate at significantly reduced capacity, with community-led services hardest hit.

Kenya has witnessed closure of at least one NSP site (Nairobi Outreach Services Trust-NOSET) and the largest OAT centre (Mathari Methadone Facility). Although nine OAT sites remain, their operational capacity is significantly reduced.

Closure of some OAT programmes and NSP sites was also reported in Tajikistan.

In Nigeria the planned expansion of NSP sites in additional states was halted.

Similarly, two OAT sites in South Africa closed, cutting off methadone for almost 5,000 clients, while several NSP sites reduced operations. In Tshwane, a single municipal government-funded programme, COSUP, absorbed nearly half of the national harm reduction services during the crisis, leading to overstretch and staff burnout.

Uganda has been left with only one operational OAT and NSP site, following the shutdown of the Kampala Region HIV Project and the Butabika MAT clinic.

In other countries, there are reports of services surviving by reducing their operations such as in Cambodia, Mozambique and Tanzania.

The human impact

The loss of skilled human resources – including peer educators, outreach workers and counsellors – has cut people who use drugs off from essential services. These roles are crucial for maintaining trust, providing health information, and connecting people to care. Other losses in supportive roles for harm reduction programmes have been reported.

Modelling suggests that an additional 3,739 new HIV infections and 6,770 new HCV infections could occur over the next year due to the combined impact of disruptions in OAT and NSP, equating to an 8.3% and 7.9% increase in HIV and HCV incidence among people who inject drugs respectively.

The wider impact of the funding crisis

Wider HIV prevention and treatment services have also been impacted, with reduced service and outreach capacity. Access to HIV testing, treatment and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) have been severely affected, putting the UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 in even further jeopardy.

Alongside the dismantling of the United States’ aid programme, there have been reductions in development assistance from several other donor countries.

This has negatively impacted the Robert Carr Fund, a crucial source of funds for global and regional community-led and civil society advocacy, as well as multilateral agencies which play functions crucial to harm reduction around the world.

A streamlined WHO and reduced UNAIDS joint programme pose great risk to the future of harm reduction. Now more than ever, we need strong community-led and civil society advocacy and a multilateral system that can lead, protect and promote harm reduction and champion evidence-based, rights-based policies and programmes for people who use drugs.

Reports of resilience

Importantly, the effects of the 2025 events have not been felt equally across countries. Those with established domestic funding for harm reduction services have shown the greatest resilience, shielding programmes and communities from the worst of the crisis.

Some governments stepped up with commitments and allocations to cover funding gaps for HIV treatment, such as in South Africa and Nigeria. However, promises to support harm reduction have yet to materialise.

Communities, as ever, have proven resilient and determined in the face of funding challenges. Peer networks have stepped in where formal systems have faltered, ensuring people know where and how to access life-saving services. Yet this resilience should not be mistaken for sustainability.

Community led organisations are doing extraordinary work with minimal support, but without dedicated and consistent funding, their ability to protect health and save lives is at risk.

Drug Policy and Human Rights

Over the past year, drug policy reform and harm reduction have continued to be addressed in international fora. Both the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) and the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) adopted landmark resolutions, reflecting a growing convergence between drug policy and human rights frameworks. Notably, the HRC adopted a resolution concerning the question of the death penalty (2025) and a resolution addressing the human rights implications of drug policy (2025)

In March 2024, the CND reached a historic milestone, for the first time explicitly recognising the role of harm reduction in Resolution 67/4. This resolution, focused on preventing and responding to drug overdose through public health measures, emphasised a balanced, evidence-based approach to drug policy.

In March 2025, the CND adopted the resolution “Strengthening the international drug control system: a path to effective implementation” (E/CN.7/2025/L.10), which established a multidisciplinary panel of 19 independent experts.

In 2024, 34 countries retained the death penalty for drug offences, and the use of capital punishment for such crimes increased compared with 2023. At least 615 people were confirmed to be executed for drug offences in 2024, marking the deadliest year on record since 2015.

Nearly 40% of all recorded executions globally in 2024 were carried out for drug-related offences.

While applications of the death penalty and executions have continued into 2025, there has been one positive development: in June of this year, the government of Vietnam removed the death penalty for certain drug-related offences.

Other country-level developments

Drug checking services were introduced in New South Wales, and there are plans to expand to Victoria marking a significant advance in evidence-based policy. Meanwhile, Queensland withdrew funding for drug-checking services and became the first Australian state to ban drug-checking.

Colombia’s second drug consumption room opened in Cali. The country also hosted the Harm Reduction International Conference (HR25) in Bogotá, welcoming over 1,000 participants from more than 60 countries to discuss, collaborate and critically reflect around the theme Sowing Change to Harvest Justice.

In Georgia, the government forced the closure of all commercial OAT programmes, transferring clients to state-run services and announcing plans to relocate all OAT sites serving around 15,000 patients to remote facilities, raising concerns about access and the quality of care.

In Mexico, the national government has reinforced prohibitionist approaches, launching a highly visible campaign against fentanyl grounded in fear and stigma, and cutting public funding for health programs, including HIV-related care. At the same time, the local Mexico City administration has taken a different path. In August 2025, it created designated cannabis consumption zones with public support services.

In the United States, on top of international cuts to harm reduction funding, the Trump Administration issued an Executive Order in July 2025 that threatened domestic funding cuts and even civil and criminal penalties against harm reduction services. This in effect reverses previous federal commitments to harm reduction.

However, the US National HIV/AIDS Strategy, which includes supportive references to harm reduction, is set to expire at the end of 2025. The Global State of Harm Reduction continues to classify the United States as a country with explicit supportive references to harm reduction in national policy documents, although this stance is now severely undermined by the Executive Order.

These developments highlight that while harm reduction continues to advance overall, in many places its coverage and scale remain limited, and in some contexts, it is newly under threat. Significant inequalities persist both within and between regions and countries in terms of availability and access. Progress also remains vulnerable to political shifts and funding constraints.

Don't miss our events and publications

Subscribe to our newsletter