The Global State of Harm Reduction 2024

download full reportmain findings

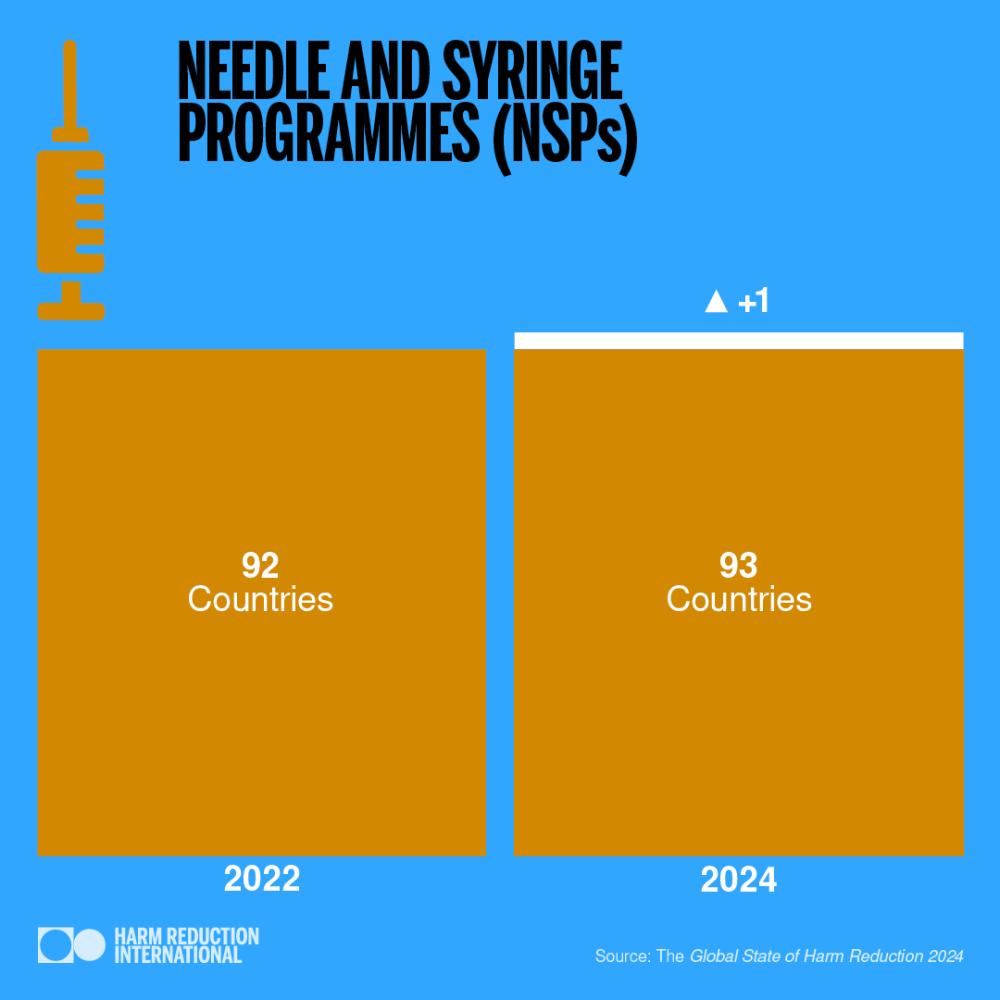

93

countries

have needle and syringe programmes

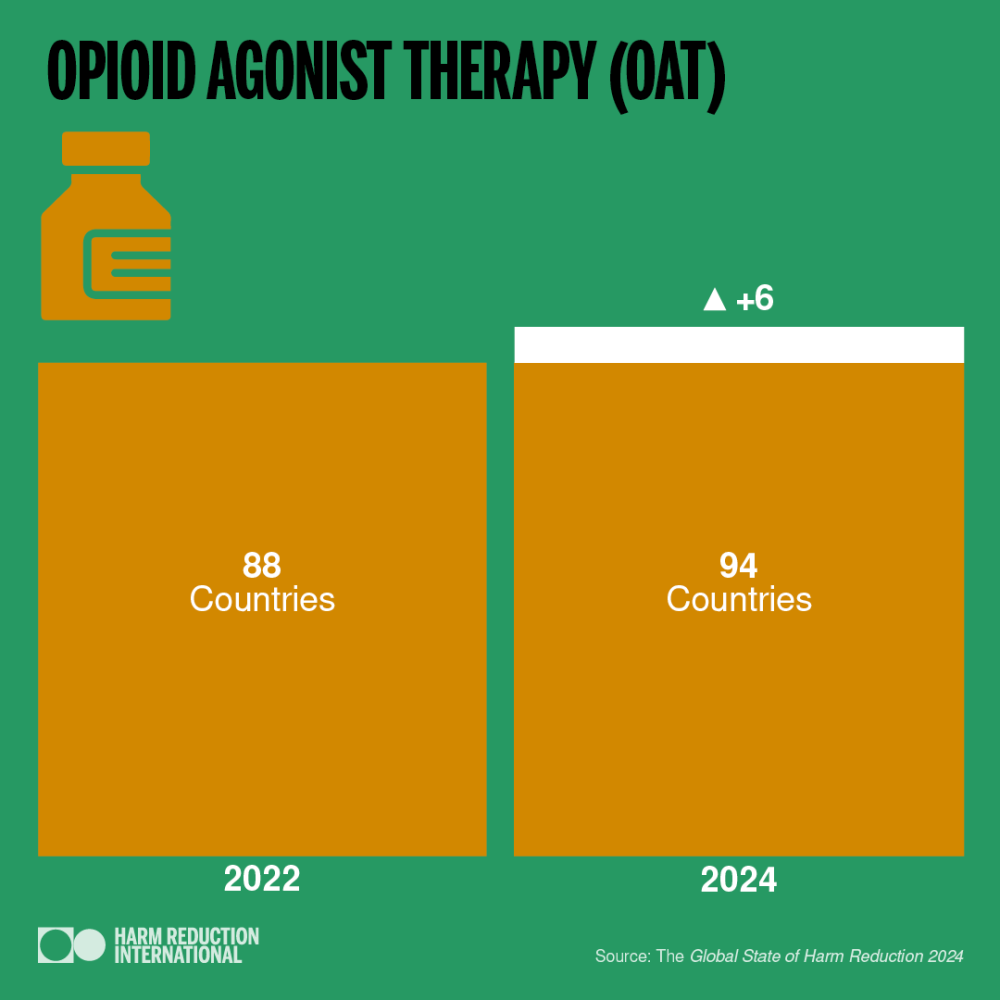

94

countries

offer opioid agonist therapy

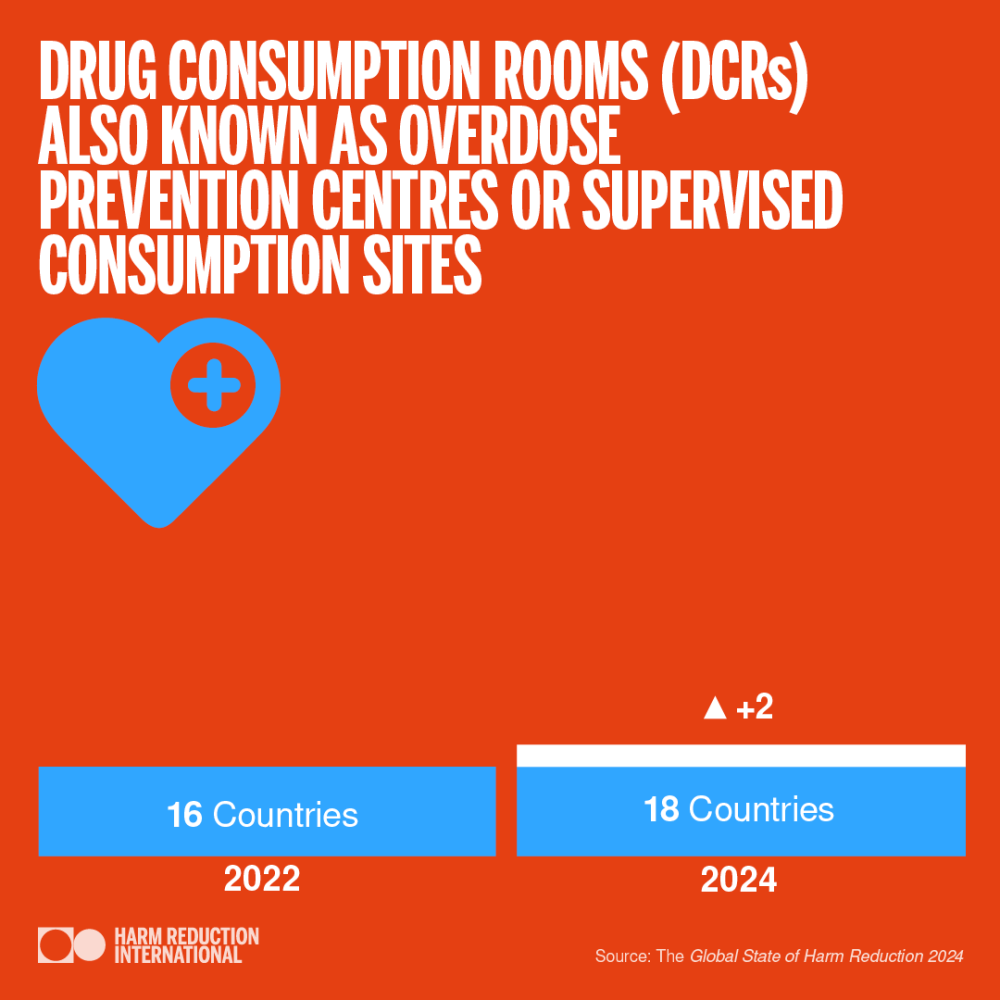

18

countries

have drug consumption rooms

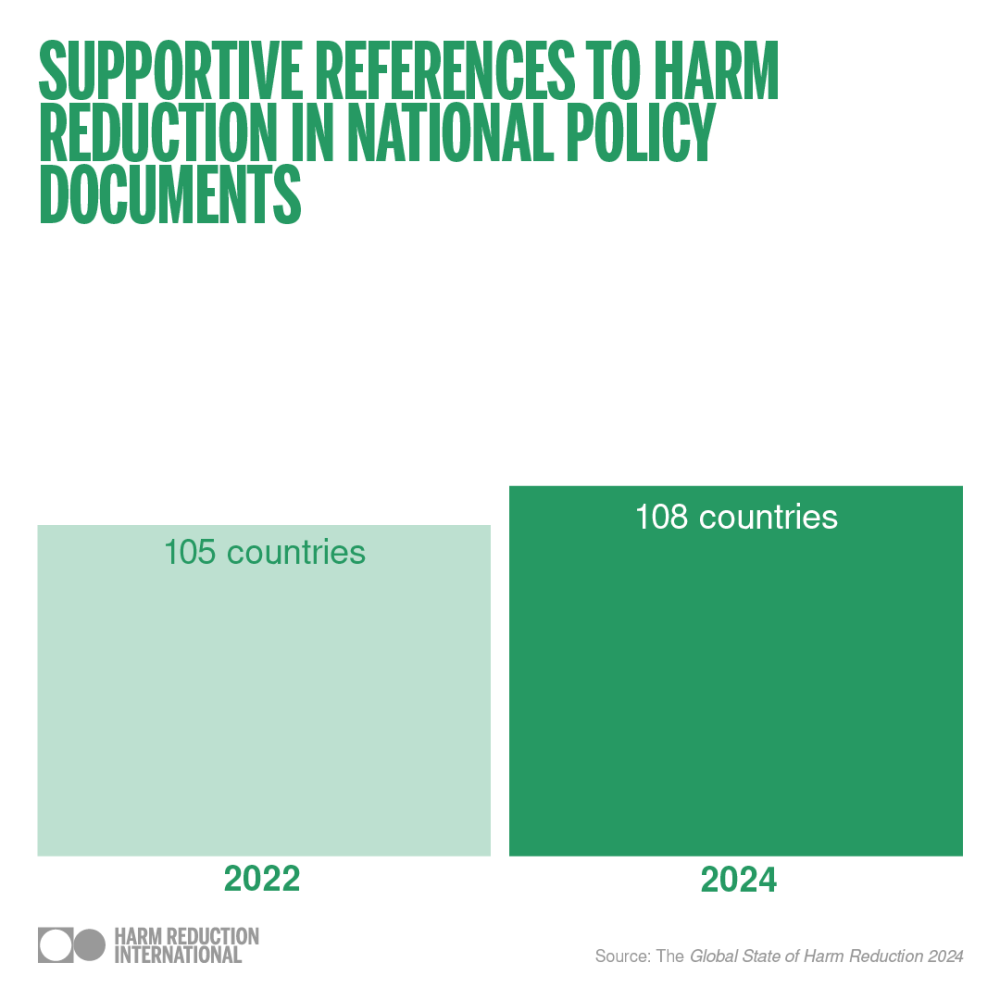

108

countries

support harm reduction in their national policies

Share this post

other languages

Introduction

The Global State of Harm Reduction is the only report that provides an independent analysis of harm reduction in the world. Now in its the ninth edition, the Global State of Harm Reduction 2024 is the most comprehensive global mapping of harm reduction responses to drug use, HIV and viral hepatitis.

The Global State of Harm Reduction has always been produced through a collaborative effort between community and civil society representatives and researchers. The report includes nine regional chapters authored by experts from each region. This year’s report differs slightly from previous editions as we emphasise key regional issues and populations that continue to be

neglected by harm reduction services.

Each regional chapter presents data on the availability of harm reduction services and addresses two key issues that require special attention. The report also includes three new thematic chapters focused on harm reduction for Indigenous people, people in prison and youth. We also continue to include data to map the implementation of viral hepatitis services for people who use drugs.

Top trends

93 countries now provide at least one needle and syringe programme (NSP), compared to 92 in 2022.

Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) programmes are now in 94 countries, compared to 88 in 2022 – although coverage remains varied and limited.

The number of countries with drug consumption rooms (DCRs) or overdose preventions centres remains very small, but it has increased from 16 to 18 since 2022. The two new countries on this list are Colombia and Sierra Leone.

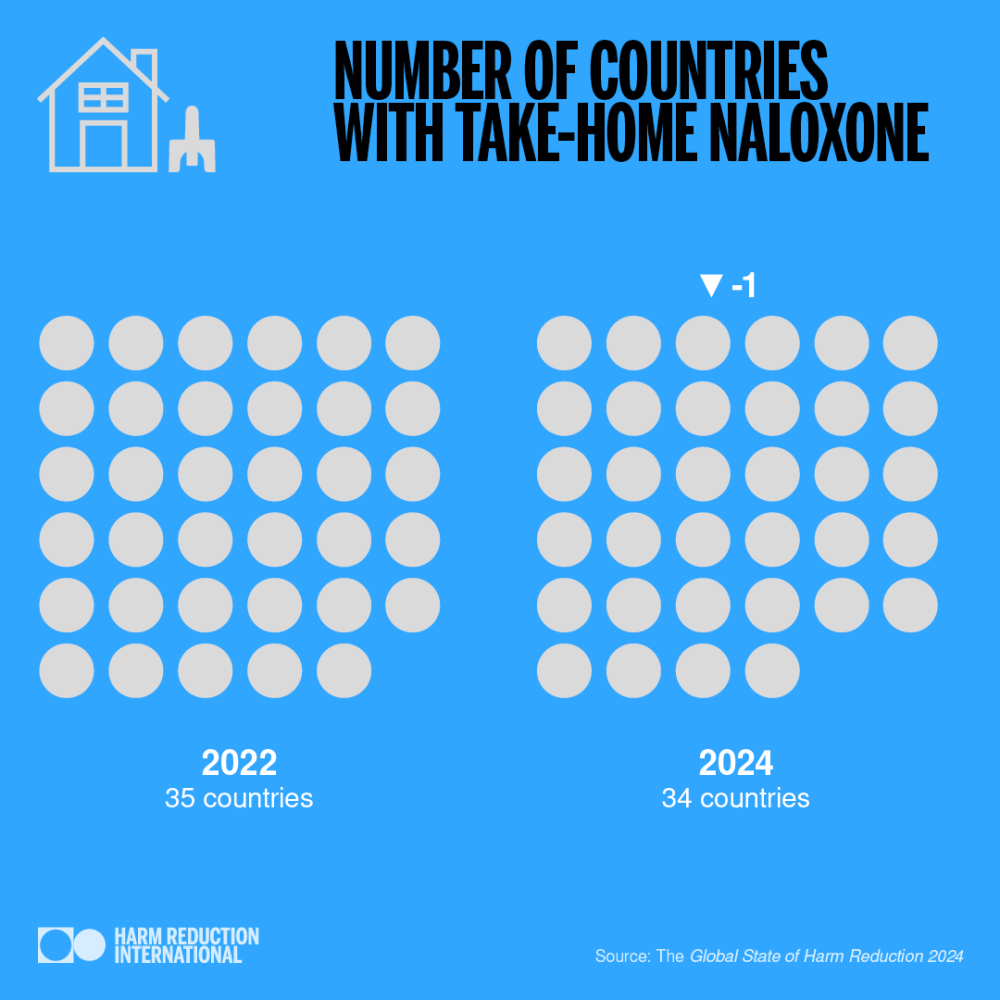

Take-home naloxone programmes are now available in 34 countries, a slight decrease from 35 in 2022.

Punitive approach continues

Overall, there has been a slight increase in the availability of harm reduction services since the Global State of Harm Reduction report in 2022. However, substantial regional differences still exist. The stigmatisation and criminalisation of people who use drugs remain significant issues. They impede access to existing harm reduction services and undermine the political and financial support needed to implement and expand these services.

108 countries include harm reduction in national policies. However, criminalisation and punitive responses to drugs remain dominant in most places. These approaches undermine harm reduction efforts and continue to fuel stigma and discrimination and deter people who use drugs from seeking vital, life-saving services. This key contradiction must be addressed for meaningful progress to be made.

Insufficient Funding

Harm reduction services such as NSP and OAT are cost-effective and cost-saving public health interventions. They improve public health outcomes and contribute to reducing the negative social and economic impacts associated with drug use. Despite this, harm reduction is seriously underfunded in most regions.

The latest research identified USD 151 million in harm reduction funding in low- and middle-income countries in 2022 – only 6% of the estimated USD 2.7 billion needed annually by 2025. This leaves a funding gap of 94%. Despite global commitments and international HIV prevention guidelines supporting the scaling up of harm reduction services, funding is woefully insufficient. Harm reduction programmes accounted for only 0.7% of total HIV funding in 2022, despite 8% of new HIV infections occurring among people who inject drugs

The number of international harm reduction donors remains small, leaving harm reduction vulnerable to their shifting priorities.

Domestic funding for harm reduction is even more fragile, and a lack of data prevents civil society from being able to monitor levels and hold governments accountable.

underserved populations

Some people who use drugs face multiple, intersecting vulnerabilities which impede their access to harm reduction services. This includes women, LGBTQI+ people, Indigenous people, migrants and people in prison. In addition to stigmatisation because of their drug use, these groups are already marginalised and discriminated against. This results in them being particularly

underserved. Young people who use drugs also face additional barriers to accessing services. Language can also be a significant barrier for migrants who need access to harm reduction services. Interpreters and multicultural mediators are needed to ensure migrants who use drugs can access harm reduction services.

Harm reduction for people aged below 18 years is still seen as a controversial issue.

There are age restrictions to accessing harm reduction services in many countries around the world. In Western Europe, where harm reduction has a longer history than other regions and the policy environment is generally more favourable, under 18s are not formally permitted to use DCRs, NSPs or drug checking services.

Indigenous people and people from other racialised communities face racism on top of stigmatisation for drug use. Rates of drug related harm are higher for Indigenous people, according to research from Canada, the USA, Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. For example, opioid overdose deaths are seven times higher for Kainai peoples in Alberta, Canada than for the general population.

Uneven geographical coverage of harm reduction services is still a serious barrier to access around the world. Even where these services exist and are recognised as important at the national level, people living in remote or rural areas still find them hard to access.

People in Prisons

Punitive drug policies have led to the overrepresentation of people who use drugs in prisons, where access to harm reduction services is even more inadequate. An estimated one-third to half of people in prison have a history of drug use.

Many people continue or start injecting drugs while in prison, and high-risk behaviours such as sharing paraphernalia and unsafe tattooing also increase in prison and other closed settings. Despite the evident need for harm reduction services in prisons, they are typically even less likely to be available than they are outside prison. For instance, only 11 countries have an NSP in at least one prison – this is just 12% of the 93 countries that provide NSPs to people outside of prison. Apart from Canada, all identified NSPs in prisons are in Eurasia (Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Tajikistan and Ukraine) and Western Europe (Spain, Luxembourg, Germany, and Switzerland). Naloxone is available in at least one prison in just 11 countries across Europe, North America and Australia.

Globally, OAT in prisons is available in at least 60 countries. However, the availability of this service varies widely between regions. In Asia, only five countries provide OAT in at least one prison. In most European and Eurasian countries, OAT is available in at least some prisons. But services are not always equally accessible within these countries. People often experience administrative and bureaucratic barriers that stop them from getting the services they need, for example, prison-based OAT being limited to people who had prescriptions before being incarcerated.

Needle and Syringe Programmes

Opioid Agonist Therapy

Countries or territories employing a harm reduction approach in policy or practice

Related resources

Don't miss our events and publications

Subscribe to our newsletter