The Cost of Complacency: A Harm Reduction Funding Crisis

download full reportmain findings

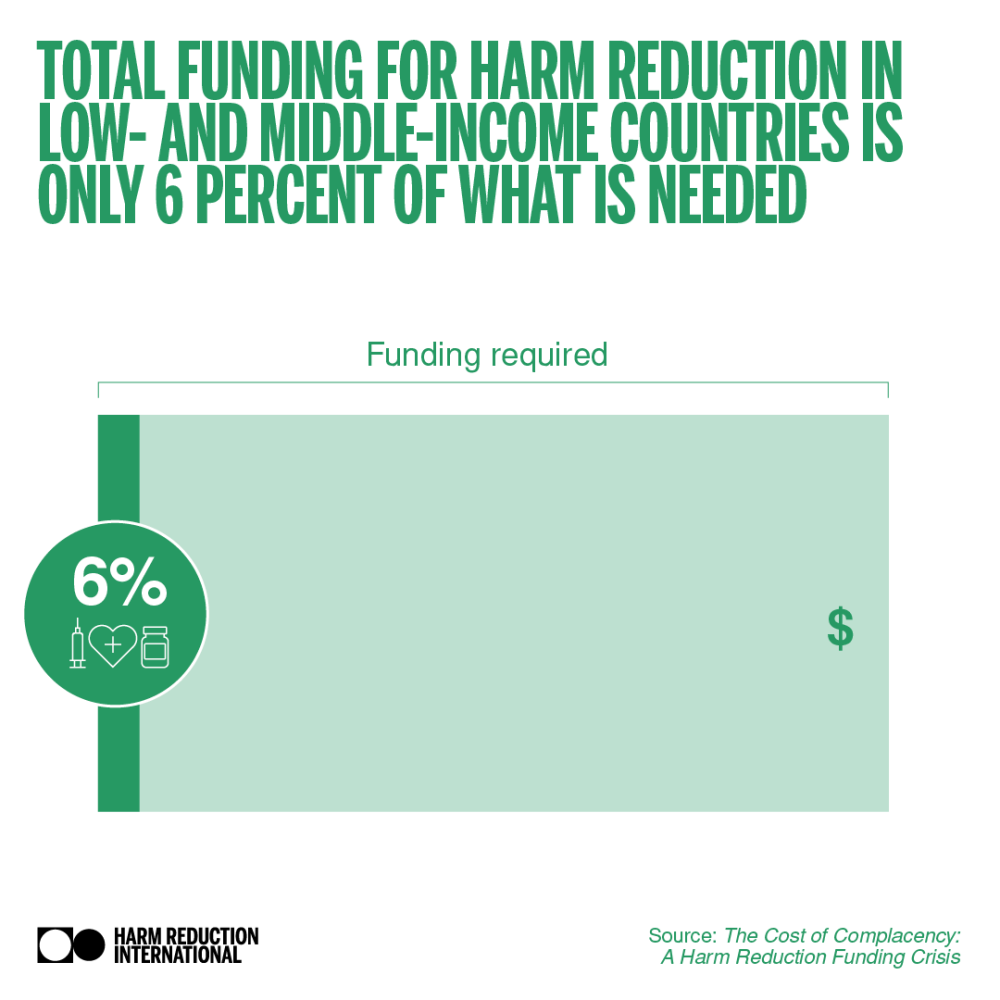

94%

funding gap

for harm reduction in LMICs

0.7%

of HIV funding

goes towards harm reduction

27

countries

invest in harm reduction domestically

fragile funding

Historically, funding for harm reduction in low- and middle-income countries has been part of the HIV response, with a comprehensive package of interventions endorsed at the highest political level as part of the global commitment to end AIDS by 2030. However, in the 15 years that Harm Reduction International (HRI) has monitored harm reduction funding, our findings have been consistently bleak. Inadequate financial support for services and for the advocacy efforts needed to drive political commitment within countries continues to prevent harm reduction initiatives being implemented at scale.

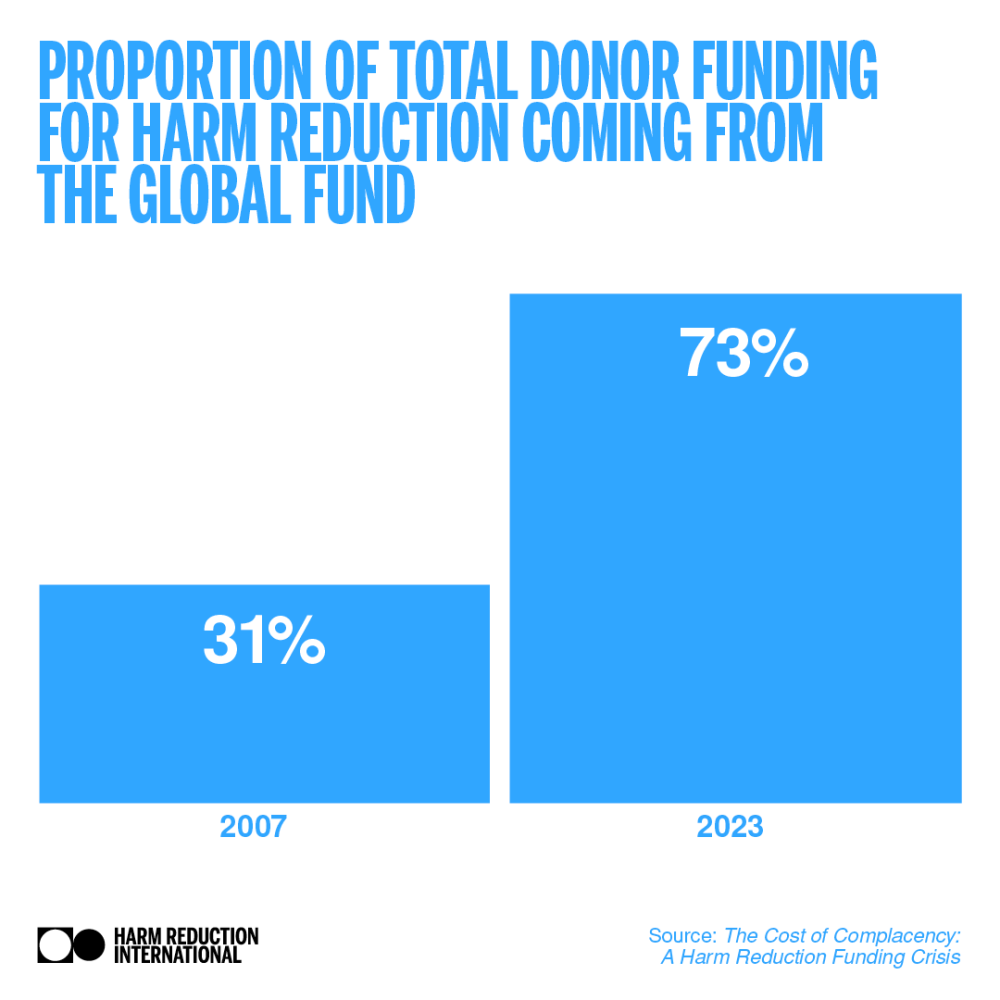

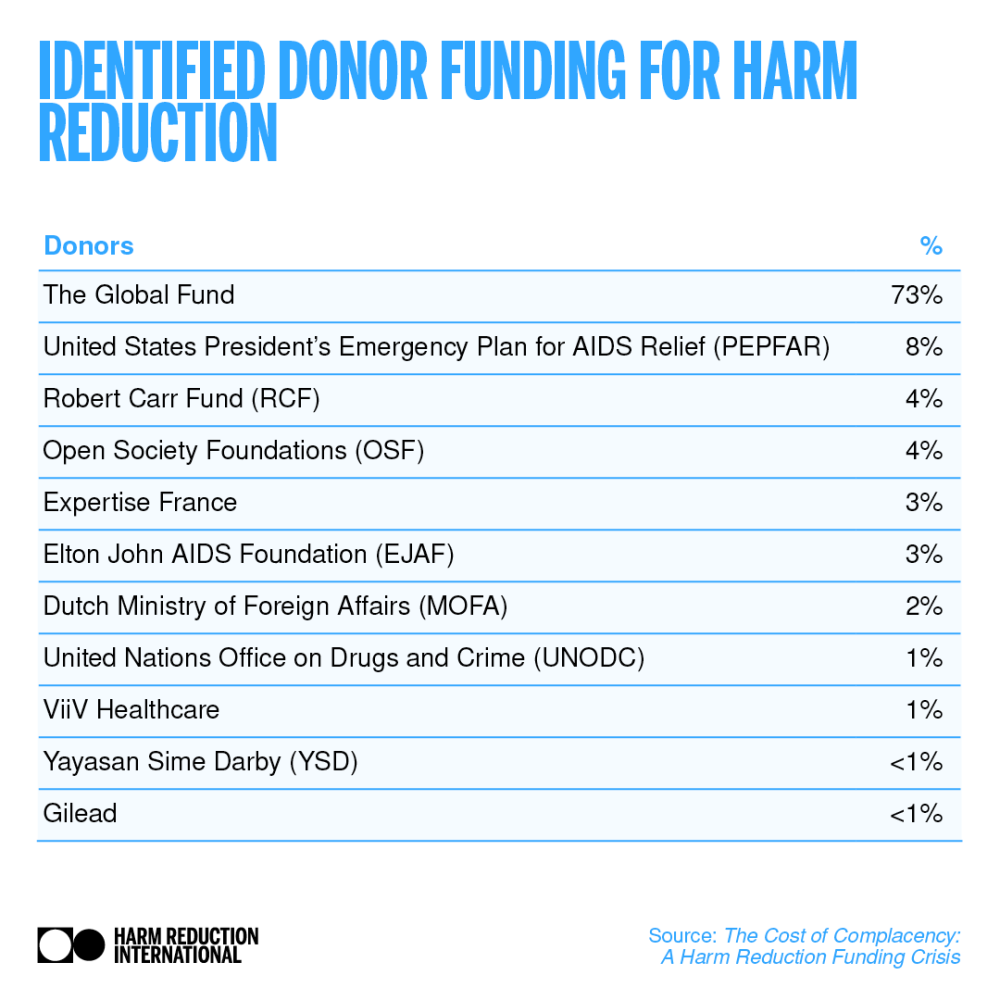

The number of international donors investing in harm reduction remains small, there is increasing dependence on the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), and harm reduction funding is vulnerable to donors’ shifting priorities. Domestic funding for harm reduction is even more fragile, while a lack of data prevents civil society from monitoring funding levels and holding governments to account. This report explores the state of harm reduction funding in low- and middle-income countries, using information collected from harm reduction donors and a desk review of literature and data on domestic funding. The findings show that, despite many high-level political commitments, we are no closer to achieving a sustainable harm reduction response.

Key findings

- Harm reduction funding is only 6% of the estimated need in low and middle-income countries.

- Community-led responses to drugs are effective but there is currently no way to hold donors accountable on funding for community-led organisations.

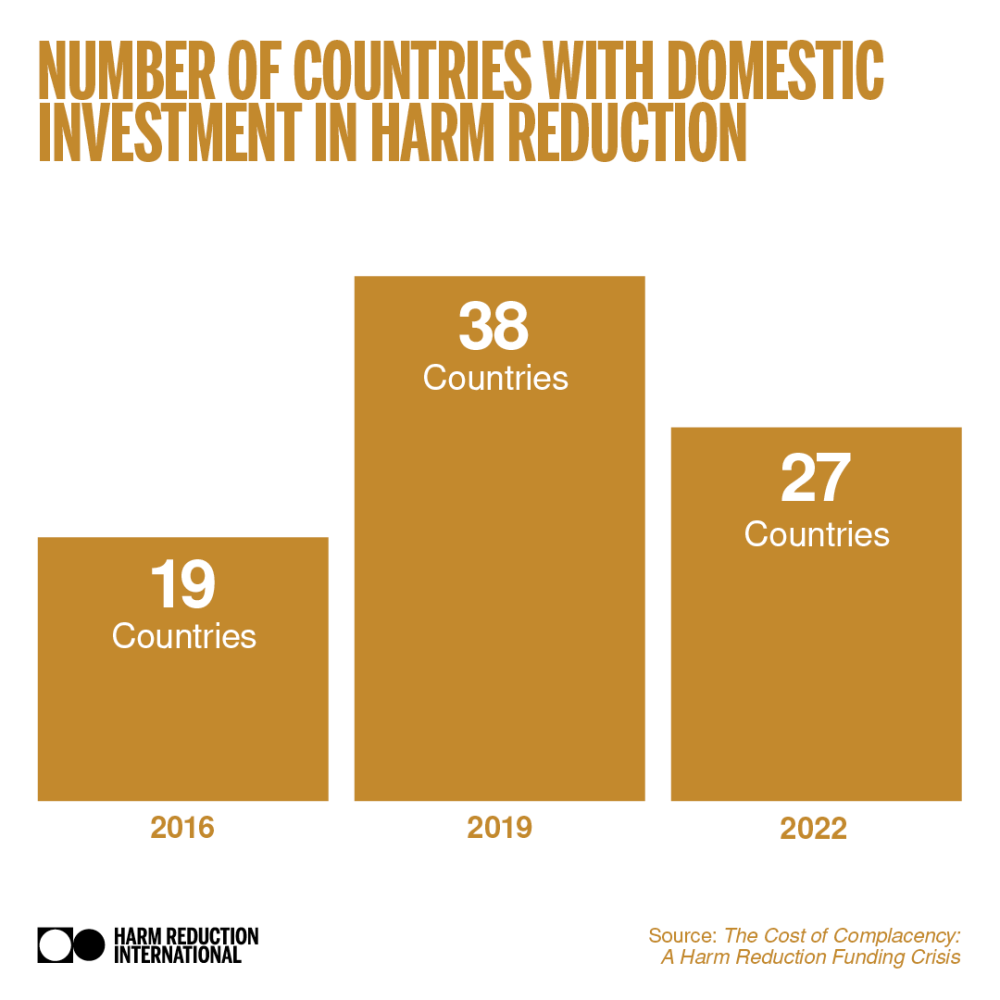

- There has been a decrease in identified domestic funding for harm reduction.

- There is little evidence of sustainable domestic harm reduction responses particularly following donor

withdrawal. - Harm reduction funding has been negatively impacted by the shift away from bilateral funding to multilateral funding.

- The Global Fund remains the largest donor for harm reduction, but it requires additional funding mechanisms to boost harm reduction funding.

global state of harm reduction

After a period of stagnation between 2014 and 2020, we have reported an increase in the number of countries including harm reduction within their national policies, up to 109 countries globally in 2023. However, only half of all low- and middleincome countries (n=67) included harm reduction in their national policies in 2023, and less than half (n=57) had at least one needle and syringe programme (NSP) or opioid agonist therapy (OAT) service operational.

Since 2020, the world has experienced several acute crises which have tested the resilience of harm reduction services. Economic, political, humanitarian and environmental crises have also put harm reduction at risk. Harm reduction services, particularly those led by the community of people who use drugs and civil society have shown their ability to reach those most in need and adapt to changing circumstances in times of crises.

political commitments aplenty

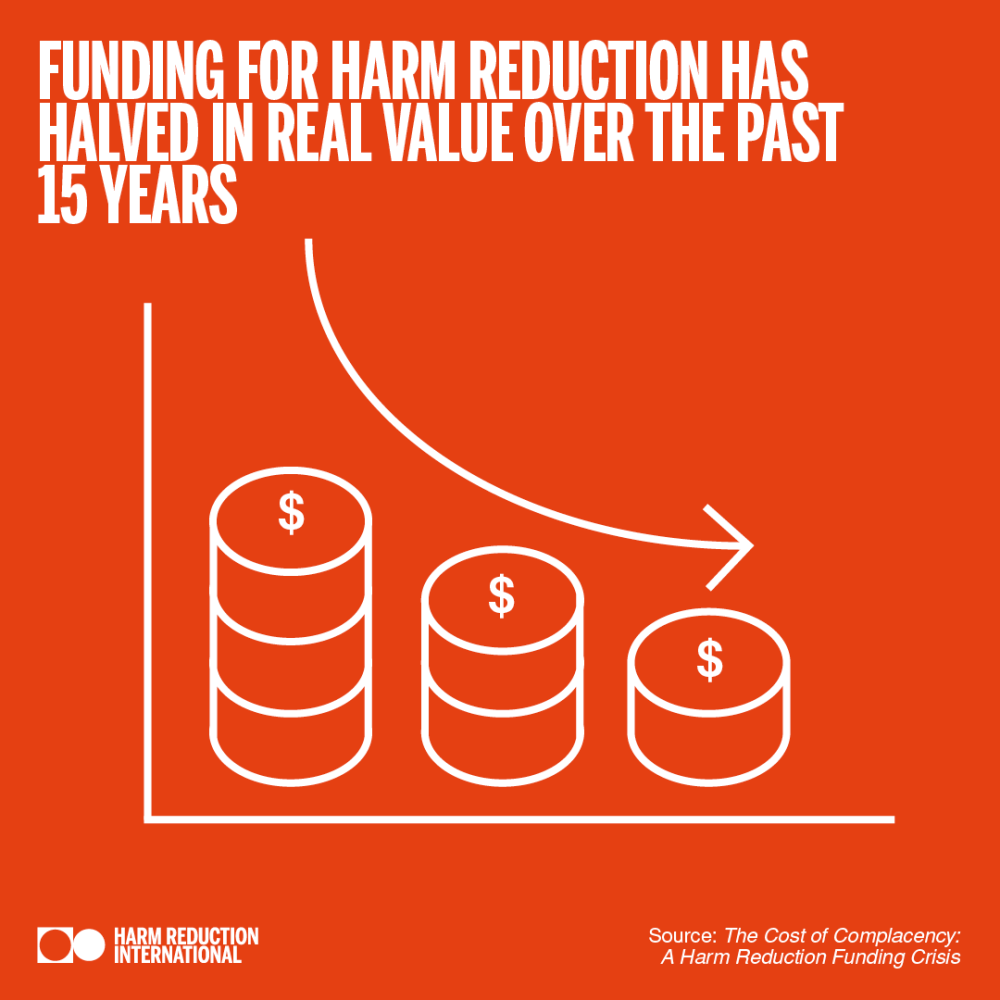

Harm reduction in low- and middle- income countries has historically been framed within the global effort to end AIDS. However, since we began monitoring harm reduction funding in low- and middle-income countries, data has consistently shown a drastic shortfall in international donor and domestic funding, far below the level required to meet globally-agreed harm reduction targets. Failure to Fund, HRI’s last funding report, identified a large reduction in harm reduction funding in low- and middle-income countries between 2016 and 2019 (from USD 188 million to USD 131 million), following a decade of stagnation in funding levels (USD 160 million, equivalent to USD 187 million in 2016 prices).

Since we last reported in 2021, harm reduction has gained further support in UNAIDS and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) global strategies. It is identified as a key component to ending AIDS by 2030 as set out in UNAIDS’ Global AIDS Strategy 2021-2026. The WHO’s global health sector strategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) for 2022-2030 further emphasise the need for an intensified harm reduction response and demonstrate harm reduction’s wider impact outside of the HIV response.

Emphasis has also increased on the need for legal and policy reform. UNAIDS’ 10-10-10 targets recognise the damaging impact of stigma and the criminalisation of key populations, including people who use drugs. The strategy sets a target for 90% of countries to have repealed punitive laws and policies by 2025. At last count, of 128 countries reporting to UNAIDS, 115 still criminalised drug use or possession for personal use. Updated guidance from WHO on key population programmes lists the removal of punitive laws and policies and other structural barriers to health services as ‘essential for impact’.

The historic adoption of a harm reduction resolution at the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs in 2024 marked the first time this forum recognised harm reduction as an important part of an effective public health response. However, spending on drug law enforcement and imprisonment continues to dwarf investment in harm reduction; with countries spending over 600 times more on punitive policies than on harm reduction. So entrenched is this approach, that even aid budgets intended to support progress

towards health and development goals are used to fund punitive drug control.

While new strategies from the two largest harm reduction donors the Global Fund’s 2023 to 2028 strategy and PEPFAR’s five-year strategy, which began in 202219 are in alignment with international commitments and guidance, it is unclear how far these strategies will translate into the action needed to kickstart harm reduction and close the funding gap. More broadly, competing priorities are contributing to shifts in donor funding and there is mounting concern among donors and implementers about fragmentation and inefficiencies within the global health architecture. This concern arises from numerous multilateral and bilateral institutions vying for resources, investing in overlapping areas and imposing excessive coordination and reporting burdens on recipient countries.

As we move closer to the target deadlines there is increased focus on the sustainability of the HIV response. UNAIDS’ HIV Response Sustainability Primer highlights the need for adequate, sustainable and equitable financing alongside enabling policies, political commitment, evidence-based programmes and people-centred healthcare and social systems. This report assesses whether global political commitments have galvanised donor and government action and measures the progress that has been made in moving towards a sustainable harm reduction response.

harm reduction funding in LMICs

This report identified USD 151 million of funding for harm reduction in low- and middle-income countries in 2022. This is more than the USD 131 million identified for 2019 in HRI’s Failure to Fund report but substantially less than the amount identified in our previous research, particularly when adjusting for inflation.

While donor investment accounted for 52% of total harm reduction funding in 2019, it constituted 67% (USD 101.6 million) of the total funding we have identified for harm reduction in 2022.

UNAIDS reports that, overall, domestic funding for HIV in low- and middle-income countries has fallen for three consecutive years. Transitions from donor to domestic funding for HIV have been delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic and other emergency situations, including increasing conflicts and subsequent humanitarian crises.35 This has led to worsening poverty, deepening debt crises and increases in the cost of programme delivery and commodities. Meanwhile, progress on human rights has stalled, and drug use continues to be criminalised and stigmatised. Spending on key populations lags far behind the estimated need across all regions but particularly in MENA. This is an alarming situation. It shows that more effort is needed to achieve sustainable financing for harm reduction, and to support underlying social enablers and health systems strengthening.

Building a Sustainable Response

There are significant barriers to building a sustainable harm reduction response that go beyond the amount of funding provided for harm reduction. While increased harm reduction funding from donors and domestic governments is essential for closing the pressing issue of the resource-needs funding gap, increasing the involvement of communities and civil society lies at the heart of a sustainable and just healthcare response.

There must be:

- Meaningful involvement of people who use drugs in donors’ decision-making processes

- Reduced barriers to funding particularly for community-led organisations

- Enhanced public financing mechanisms for community-centred health responses

- Decriminalisation of drug use

Recommendations

- Harm reduction donors and governments must make substantial additional investments to meet global goals to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.

- Funding for advocacy should be increased to help drive the drug law and policy reform required for sustainable harm reduction responses.

- International donors and governments must invest in community-led organisations as part of national health systems to create and protect resilient and sustainable harm reduction programmes.

- International donors should support governments to establish the financing mechanisms required for domestic funding of harm reduction.

- Harm reduction needs to be viewed as broader than disease prevention.

Related resources

open letter to the who

Don't miss our events and publications

Subscribe to our newsletter