The Death Penalty for Drug Offences: Global Overview 2024

download full reportmain findings

34

countries still retain the death penalty for drug offences

615+

people executed in 2024

377+

death sentences imposed in 2024

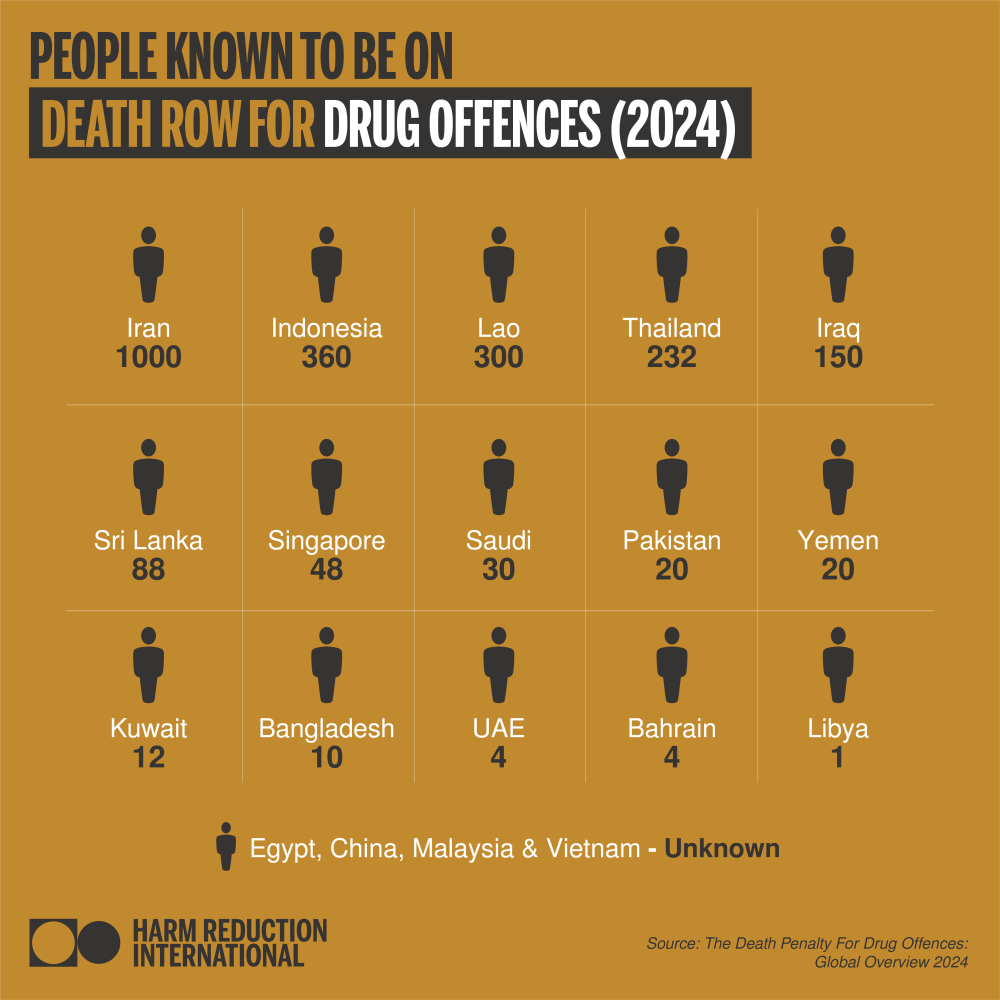

2300+

people on death row for drug offences worldwide

Introduction

Harm Reduction International (HRI) has monitored the use of the death penalty for drug offences worldwide since our first ground-breaking publication on this issue in 2007. This report, our 14th on the subject, continues our work of providing regular updates on legislative, policy and practical developments related to the use of capital punishment for drug offences, a practice which is a clear violation of international human rights and drug control standards. The Death Penalty for Drug Offences: Global Overview 2024 presents an analysis of key developments, with a focus on analysing and disseminating available figures and trends on drug-related executions and death sentences.

A dedicated section summarises the findings of HRI’s report, Gaining Ground: How states abolish or restrict application of the death penalty for drug offences, which explores how 17 countries have either abolished or limited the use of the death penalty for drug offences. This section reviews reform processes, identifies key actors and factors – social, political, cultural and economic – that have catalysed change towards abolition, and provides recommendations which can be of use to advocates in a time of exceptional recourse to the death penalty as a tool of drug control.

HRI opposes the death penalty in all cases without exception.

Global Picture

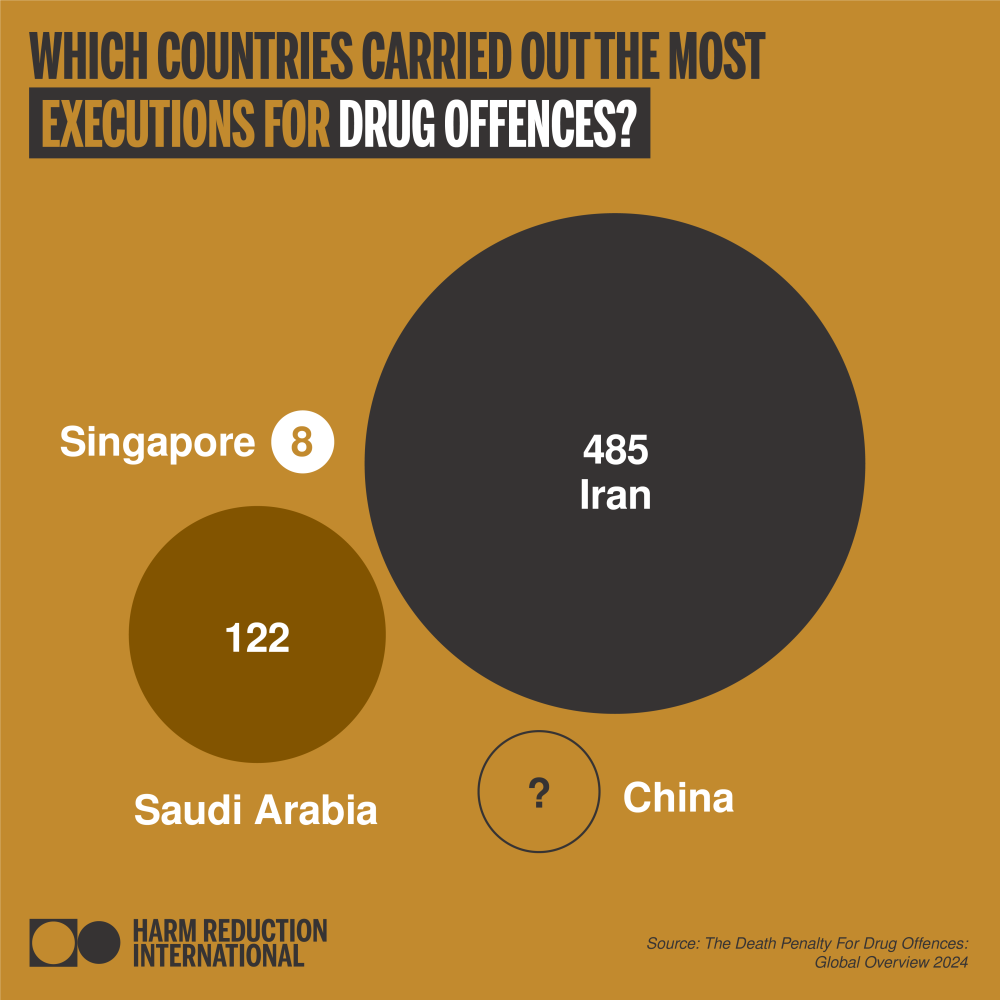

After cautious optimism between 2018 and 2020, HRI has been reporting a steady increase in known drug-related executions since 2021. This trend reached crisis levels in 2024. With 615 people confirmed to have been executed for drug offences, 2024 is the deadliest year on record since 2015. Known executions have risen by 32% from 2023, and by a staggering 1950% from 2020, the year with the lowest figure on record. Notably, the figure of 615 known executions does not include the hundreds – if not thousands – of drug-related executions carried out in China, North Korea and Vietnam, where state censorship prevents us from realistically documenting how many people have been killed for drug offences.

Executions were confirmed or assumed to have taken place in six countries: China, Iran, North Korea, Singapore, Saudi Arabia and Vietnam. Iran is responsible for 79% of all known drug-related executions (485) and thus remains the world’s biggest executioner for drug offences, together with China. The highest increase in executions was recorded in Saudi Arabia, where 122 people were executed for drug offences. This is a 6000% surge from 2023 (when two people were executed for drug offences), and the highest figure ever recorded in the Kingdom, signalling a renewed commitment to this barbaric practice as a tool of drug control. A jump in executions also occurred in Singapore, where eight people were hanged for drug trafficking between August and November 2024 alone.

This is an extremely small group of countries, responsible for an incommensurate number of executions. This signals an alarming determination to retain this inhumane punishment, despite its ineffectiveness and incompatibility with international law and standards.

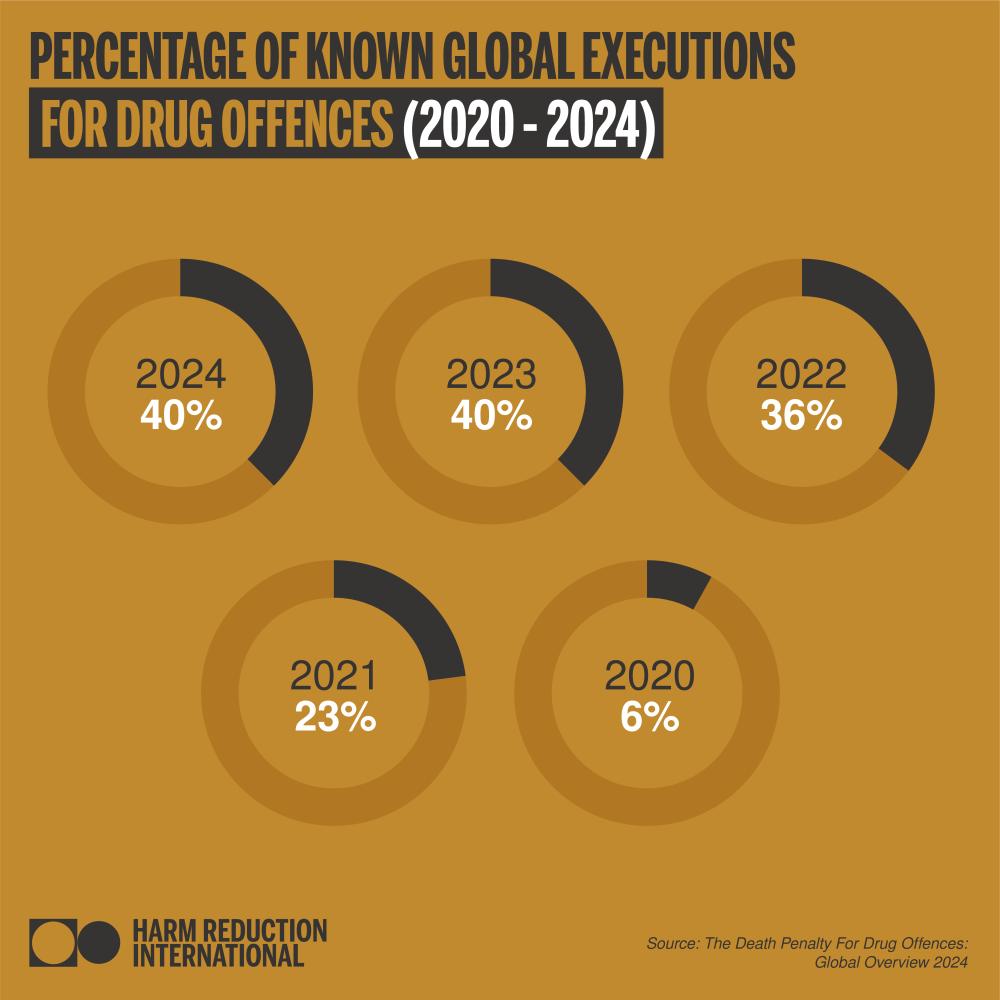

These figures also confirm that drug control has become a key driver of the imposition of capital punishment worldwide and an obstacle to global abolition of the death penalty. Around 40% of all known executions carried out in 2024 – almost one in two – were for drug offences. The same trend is mirrored at the domestic level: drug offences were responsible for the majority of known executions in Iran (52%) and Singapore (89%), and for the majority of death sentences confirmed in Indonesia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam. Available figures on death row populations paint a similar picture.

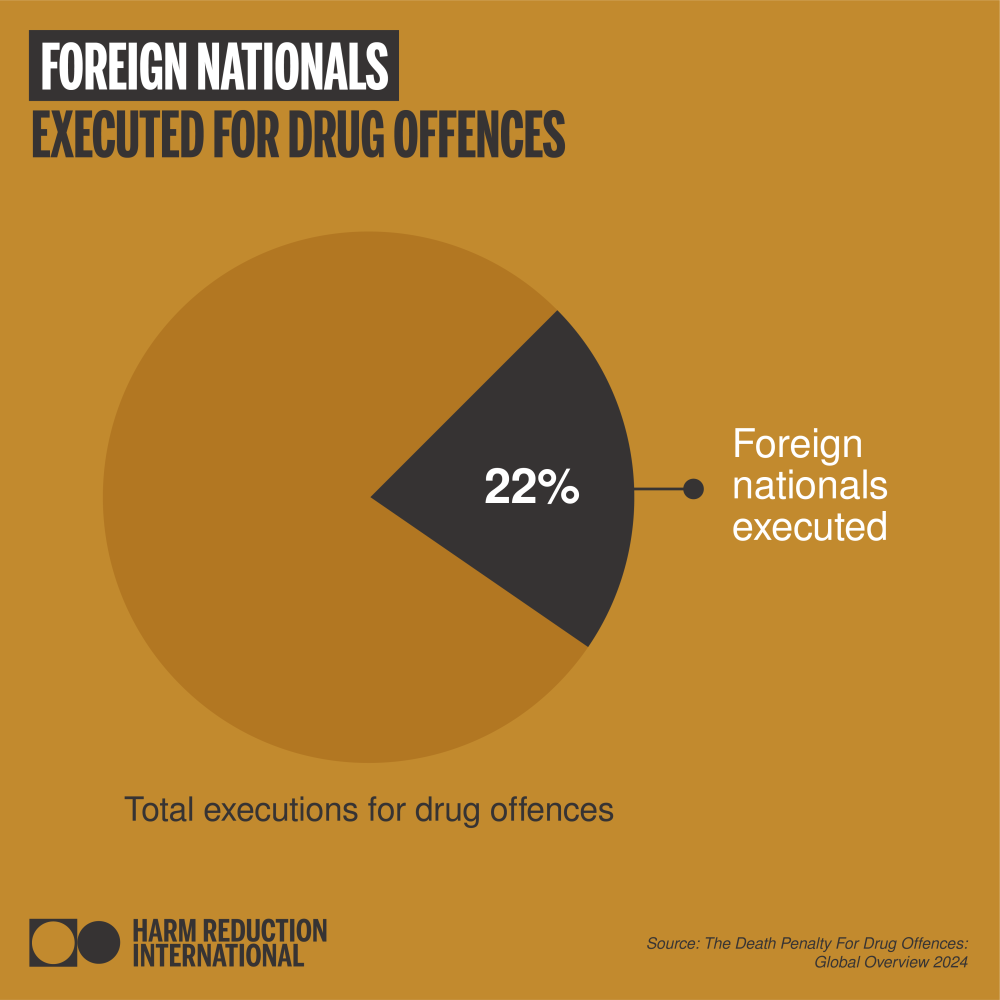

Among those executed, at least 18 were women and 136 – more than one in five – were foreign nationals. The finding on foreign nationals is a stark reminder of the overrepresentation of this group among people sentenced to death and executed for drug offences, driven both by marginalisation and the unique barriers of navigating foreign criminal legal systems.

At least 377 people were sentenced to death for drug offences in 17 countries, of which 11 were women and 20 foreign nationals. These figures are likely to be only the tip of the iceberg due to the widespread lack of updated and disaggregated information (particularly on ‘high application’ countries, such as Iran and Saudi Arabia) and in light of state practices concerning executions. While a slight decrease in death sentences for drug offences was observed in countries such as Malaysia (thanks to the 2023 reform which removed the mandatory nature of capital punishment, giving judges full discretion in drug trafficking cases), Indonesia and Vietnam (possibly due to gaps in monitoring), the situation has deteriorated in others. This has been most notable in Iraq where officials claimed over 140 death sentences were imposed for drug offences in 2024 due to large-scale anti-drug operations. If confirmed, this would be a 658% jump in drug-related death sentences from 2023. Worryingly, a record number of people were executed in Iraq in 2024, mostly for terrorism. These executions often took place en masse, following trials tainted by torture and due process violations. These developments combined suggest drug-related executions may start happening in the country soon.

In Pakistan, death was completely removed as a possible sentence for drug offences in 2023. However, Justice Project Pakistan reported three death sentences for drug-related offences in 2024. This is a unique situation, and it highlights the urgency of judicial sensitisation and reform rollout throughout the country.

These figures are of extreme concern to the thousands of people who remain on death row for drug offences in at least 19 countries, many of whom are considered to be at imminent risk of execution.

Executions and death sentences have not taken place without resistance. Protests and criticism by civil society, people on death row and experts were recorded in many retentionist countries and beyond, with those involved sometimes at great personal risk. In Singapore, peaceful activism and monitoring have been met with what many – including HRI – denounce as harassment and intimidation. In Iran, people on death row have defied the regime and launched the No Executions Tuesdays campaign, going on hunger strike once every week since January 2024 to attract attention to their desperate situation.

Regrettably, grassroots activism has not been supported at the institutional level. In 2024, the international community failed, once again, to hold retentionist countries accountable for such blatant violations of human rights and drug control law and standards. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and UN human rights experts harshly condemned executions in Iran, Saudi Arabia and Singapore and called for as did the European Union, Norway, Switzerland and even the USA. However, no practical consequences ensued. Worryingly, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and many countries remained silent, despite the dramatic pace of executions, and actively cooperated in antitrafficking operations with countries that engage in this illegal practice. Far from being sanctioned for its actions, Saudi Arabia was awarded with hosting the 2034 World Cup, in a move that human rights activists vocally condemned.

The reforms that took place in 2023 in Pakistan and Malaysia had raised hopes that change is possible when spaces for dialogue open and governments can move beyond ideology. But the record-high number of executions confirmed in 2024 are a cry for help and act as a testament to the international community’s failure to take swift and concerted action against this abusive practice.

Ending the death penalty cannot be achieved without substantial drug policy reform at the national level and a critical assessment of bilateral and international anti-narcotics cooperation. There is an urgent need to interrogate the role of a multilateral ecosystem which should be at the forefront of this fight, but too often remains silent and therefore complicit. The determination of retentionist countries signals that, while change must be guided by local actors, it cannot only come from within. It requires a strong, sustained and coordinated response, and it cannot be delayed further.

Related resources

Don't miss our events and publications

Subscribe to our newsletter