The Death Penalty for Drug Offences: Global Overview 2018

download full reportmain findings

35

countries retain the death penalty for drug offences

91+

people were executed in 2018

149+

death sentences given in 2018

7000+

people are on death row for drug offences worldwide

Introduction

Harm Reduction International has monitored the use of the death penalty for drug offences worldwide since our first ground-breaking publication on this issue in 2007. This report, our eight on the subject, continues our work of providing regular updates on legislative, policy and practical developments related to the use of capital punishment for drug offences, a practice which is a clear violation of international law.

Executive Summary

The death penalty for drug offences is a clear violation of international human rights law. Numerous international authorities and legal scholars have reaffirmed this point, including the UN Human Rights Committee as recently as 2018.

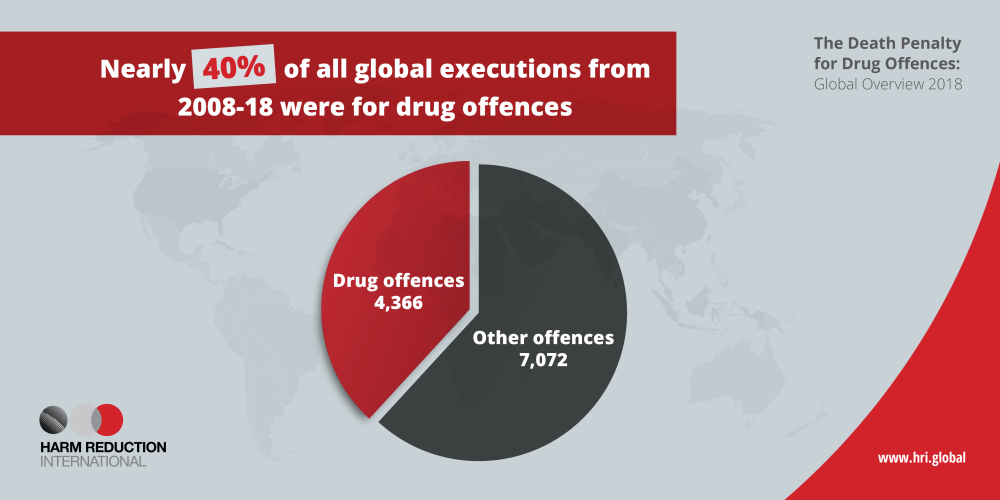

Since Harm Reduction International began monitoring the use of this abhorrent practice in 2007, annual implementation of the death penalty for drug offences has fluctuated markedly. Over 4,000 people were executed globally for these offences between 2008 and 2018, with executions hitting a peak above 750 in 2015 (excluding China and Vietnam, where these figures are a state secret). Notably, 2018 figures show a significant downward trend, with known executions falling below 100 globally.

Iran, among the most prolific executioners for drug offences, passed reforms in 2017 which resulted in a drastic reduction in the implementation of the death penalty. After a bloody stretch from 2015-2016, there were no executions (for any offence) carried out in Indonesia for a second consecutive year, and Malaysia – once among the most resolute supporters of the death penalty, including for drug offences – committed to total

abolition of the death penalty in 2018.

Yet, while executions are falling, thousands of people remain on death row for drug offences. A number of these people are at the lowest levels of the drug trade, socio-economically vulnerable, are tried without due process and/or have inadequate legal representation. In short, it appears that the death penalty for drug offences is primarily reserved for the most marginalised in society.

Other events in 2018 show that for every progressive step, there is a regressive counter-narrative. In Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, populist rhetoric against the ‘threat’ of the ‘drugs menace’ has seen leaders push for expansion or implementation of the death penalty, while governments in the Philippines and United States (among others) pointed to capital punishment as an essential tool to confront drug trafficking or public health emergencies.

There is no evidence that the death penalty is an effective deterrent to the drug trade – in fact, according to available estimates, drug markets continue to thrive around the world, despite drug laws in almost every country being grounded in a punitive approach. The response to drug use and the drug trade remains heavily politicised, frequently resulting in a rejection of evidence, even when brutal crackdowns are shown to inflict countless harms and rights violations on society.

In December 2018, a record 120 countries voted in favour of the Resolution on a moratorium on the use of the death penalty at the 73rd Session of the UN General Assembly,2 and since 2008 the number of abolitionist countries crept up from 92 to 106 in 2017.3 This is a positive trend, but when countered by inflammatory political rhetoric, progress is fragile at best. Governments must ground their drug laws in rights, dignity and evidence, and do away with the death penalty once and for all.

Don't miss our events and publications

Subscribe to our newsletter